Innovation and Coaching: The Keys to Successful Literacy and Life Ready Skills

At engage2learn, we recognize that early literacy development is crucial to the acquisition of reading and life ready skills; to best support all meaningful educational partners in this effort, including parents, teachers, and stakeholders alike, we believe that innovative literacy initiatives and job-embedded, professional coaching are the keys to a successful literate society.

The Critical Years for Literacy Development and Why It is So Challenging

It is no surprise that literacy development remains a focal point of improvement for most educational institutions. In fact, the National Institute for Literacy identifies reading “as a gateway to future success in school and in life,” yet an astonishing 36 million American adults can neither read nor write above a third grade level, according to national, empirical research compiled by ProLiteracy (2017). Moreover, the most recent findings from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which is given every two years to students in fourth and eighth grades, indicate that only 35 percent of public school students are performing at or above the proficient level in reading (2017). Perhaps authors Kirsch, Jungeblut, Jenkins, & Kolstad put it best in their assertion: “We as a nation must respond to the literacy challenge, not only to preserve our economic vitality but also to ensure that every individual has a full range of opportunities for personal fulfillment and participation in society,” (2002). At engage2learn, we recognize that early literacy development is crucial to the acquisition of reading and life ready skills; to best support all meaningful educational partners in this effort, including parents, teachers, and stakeholders alike, we believe that innovative literacy initiatives and job-embedded, professional coaching are the keys to a successful literate society.

In Early Literacy: Leading the Way to Success, the National Institute for Literacy further identifies the years from birth to age five as the most critical for students’ development: “Learning to read begins well before children enter school,” (2007). Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell—pioneer researchers, professors and authors in the specific field of literacy—have notably acclaimed, “Good first teaching is the foundation of education and the right of every child,” (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996). Nevertheless, throughout her 27 years of experience in public education, Chief Executive Officer Shannon K. Buerk has concluded that “learners thrive in classroom environments that stimulate critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving and inquiry. Unfortunately, they spend most of their time in teacher-directed classrooms where they are practicing concepts that they have already mastered.” This notion translates into the early literacy standards of alphabet knowledge, phonological awareness, phonemic memory, print concepts, and visual processing, which have been taught, historically, through blanketed repetition and memorization initiatives. Highly differentiated reading instruction, thus, is pivotal to young learners’ success. Given the above-referenced statistics on national literacy rates, our traditional methodologies and instructional pedagogy for developing a literate society are failing at an alarming rate. Though the words “innovation” and “literacy” are rarely mentioned together, both are imperative for contemporary literacy development with the infusion of such life-ready skills as autonomy, collaboration, and communication at the forefront.

Parental Involvement and Early Literacy Development

As early theorist Edmund Burke Huey states in his famous work The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading, “It all begins with parents reading to children,” (2000, p. 8) Throughout Parental Involvement: Key to Leaving No Child Behind in Reading, author Timothy Rasinski also discusses the critical influence of a student’s family upon his or her literacy development in his article published in the New England Reading Association Journal (Rasinski, 2003). Expressing his personal theory on the subject, Rasinski says, “I think parental involvement in children’s literacy development is crucial to children’s success in reading and other academic learning, from kindergarten through high school and beyond,” (2003, p. 2). Moreover, he states, “We need to provide parents with appropriate content and instructional work they can implement with their children,” (2003, p. 3).

Additionally, authors Dennis and Horne identify crucial elements of early literacy development in Strategies for Supporting Early Literacy Development, yet they maintain, “Family members have the best opportunity to support their children’s development of literacy skills,” (2011, p. 38). Similarly, Beatson suggests omitting the scientific terminology of literacy development with families and, instead, focusing on potential “literacy events,” which she cites as letter writing, meal preparation, “Thank You” cards, shopping lists, menus and even normal conversation. In short, she concludes: “In today’s society, family literacy begins with reading aloud to children and extends to encompass any literate event that the family is involved in,” (2000, p. 9). Simple, everyday tasks in a family’s life could make a significant impact upon their children’s learning if they simply seize the opportunity to make it a learning experience.

Literacy Development with Students of Poverty

Unfortunately, the Center on Children and Family notes that “fewer than half (48 percent) of poor children are ready for school by age five, compared to 75 perfect of children from moderate to high incomes,” (Isaacs, 2012). In fact, it has been estimated that students of poverty have nearly 4 million fewer words in their vocabulary by age five than their wealthier peers, and the “word gap” remains a tremendous challenge for primary literacy educators (Gilkerson et al, 2017). Dr. Ruby K. Payne—a field expert in educating students from various economic classes and thus overcoming the “hurdles of poverty”—offers invaluable resources for servicing under-resourced students in her acclaimed work, Research-based Strategies: Narrowing the Achievement Gap for Under-Resourced Students. As she points out, “Lack of personal, social, and material resources can create specific challenges for students, as well as for their schools and communities;” therefore, she concludes, “Educators are key: Teachers are integral to the lives of so many young people who can and will achieve success if we understand them and understand how to guide and teach them,” (Payne, 2010).

While establishing a functional, beneficial home-school connection can be challenging with students of lower socioeconomic status, research indicates that it should not be a deterrent as it is possible. In fact, former journalist and educational reporter Karin Chenoweth compiles examples of academic achievement in unexpected schools in her work It’s Being Done. Answering the common questions, “Can schools help all children learn to high levels, even poor children and children of color,” Chenoweth provides real-life success stories from some of America’s most underprivileged, public institutions (Chenoweth, 2007). Regardless of one’s socioeconomic status, Rasinski points out, “If parents are made to feel that they have an important role to play in their children’s literacy development…they are most likely to get involved and stayed involved throughout their children’s school years,” (2003, p. 2).

Innovation and Literacy: One School District’s Answer

Dr. David Vroonland, Superintendent of Mesquite Independent School District in Mesquite, TX, values students, their families, AND the district’s teachers. In 2015, Mesquite ISD began a concentrated focus on early literacy with a resolute goal of ensuring that all young learners read on level by third grade within their total district population of 40,945 students, including 75.1 percent classified as economically disadvantaged. Dr. Vroonland was adamant the approach be founded upon an ownership model, wherein individual teachers must research, design, and lead the instructional innovations that would, thereby, increase student literacy. To summarize this ideal learner experience identified by the Mesquite community, Dr. Vroonland proclaimed:

Innovation in education is being highly responsive and fearless to meet the needs of students versus being compliant. Building a sense of ownership gives people flexibility to respond to the needs of the students. Being innovative is not about invention. It’s about doing what is best for our schools. We are moving from being fearful to being fearless.

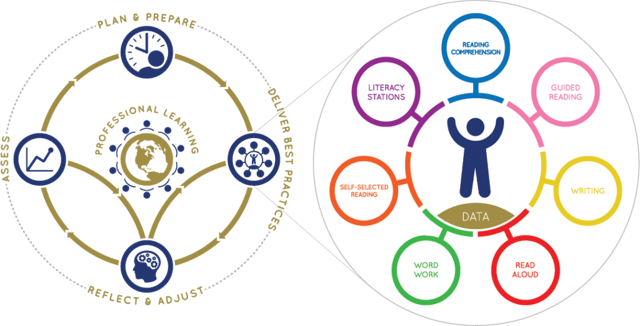

As a result, the district used a three-pronged strategy: (1) teacher-led design work of the Mesquite ISD Literacy Framework, (2) an external partnership with engage2learn (e2L) to provide teacher coaching on self-selected, literacy instructive goals and coaching for literacy leaders, and (3) a district-wide compensation program that would allow teachers to eventually earn as much as assistant principals without leaving the classroom. Mesquite ISD, in partnership with e2L, then developed a comprehensive learning framework centered around 12 high-yield educational strategies and encompassing seven essential components to literacy development. Similar to to the widely-aspired notion to develop the “whole child,” Mesquite ISD refined the concept of growing literate, future-ready learners through the laser focus on this initiative.

Mesquite ISD Learning Framework & Literacy Components

During the three-year rollout, which extended from the 2015-2016 academic year to 2018-2019, 120 prekindergarten through second grade classrooms implemented the Mesquite ISD Literacy Framework each year. Teachers were provided seven individualized coaching sessions in year one of implementation by e2L certified eGROWE coaches and five individualized coaching sessions in year two and beyond of implementation by the certified district coaches, who were trained by engage2learn using the research-based eGROWE coaching model. The initial responsible rollout has now been extended to include upper elementary, middle, and high school classrooms for an even greater impact upon learner achievement and engagement using the Mesquite ISD Learning Framework.

Job-embedded Coaching is Key

Mesquite ISD is seeing substantial growth in literacy, specifically in their second grade students who are going into third grade. Recent data from e2L coached classrooms indicated that 87.19 percent of their learners are reading on grade level, compared to just 78.13 percent in non-coached classrooms. Furthermore, learners identified as “at risk” in literacy standards are moving from Tiers 3 and 2 to a Tier 1 because of the foundational, differentiated instruction implemented with the Mesquite ISD Literacy Framework and the job-embedded professional development that supports teachers’ implementation efforts. In 2017 alone, 268 kindergarten students who entered school “at-risk” left for first grade on track!

In Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, award-winning author Daniel Pink cites autonomy, mastery, and purpose as essential factors for success both professionally and personally (2009). That is, honing one’s desire to be self-directed, tapping into that itch to keep improving at something that is of importance, and serving something meaningful beyond oneself, respectively (2009). Dr. Vroonland’s approach to valuing Mesquite ISD teachers and ensuring that they have each of the above-mentioned motivational traits within their classrooms has resulted in increased teacher engagement, retention, and job satisfaction.

In a 2017 Mesquite ISD survey, 95 percent of staff responded that the district supported their professional learning needs and 89 percent felt the district had a culture that maximized human capital. “This type of model results in teachers working harder, but they’re happier because they’re being treated as professionals. They’re being respected as people who are quite capable of taking students to great heights in their education,” says Dr. Vroonland. After all, John Whitmore, author of Coaching For Performance: GROWing People, Performance and Purpose, notes this observation as the foundation for such job-embedded professional development: “Coaching focuses on future possibilities, not past mistakes,” (1992).

Cultivating an innovative learning environment with a focus on comprehensive literacy development in classrooms district-wide is changing the trajectory of students’ lives in Mesquite Independent School District and, thus, producing a more literate community as a whole. “Read, Play, Talk” has been adopted as a community-wide initiative since the development of the Literacy Framework by Mesquite ISD and in partnership with engage2learn; this family-inclusive reminder is visible in most every public realm and encourages a systemic culture shift for an entire urban population. Mesquite ISD has achieved great results from their “Read, Play, Talk” initiative by engaging parents and community partners, utilizing job-embedded coaching, and focusing on learner-centered innovations with literacy practices. These practices hold promise for other educators who want to impact student literacy with innovation and stakeholder engagement.

Resources

- Beatson, L. (2000). Research on parental involvement in reading. Northeastern Educational Research Association, 36, 8-10.

- Buerk, S. (2016). Inquiry learning models and gifted education: A curriculum of innovation and possibility. In T. Kettler (Ed.) Modern Curriculum for Gifted and Advanced Academic Students. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press Inc.

- Chenoweth, K. (2007). It’s being done: academic success in unexpected schools. First edition.Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Dennis, L., & Horn, E. (2011). Strategies for supporting early literacy development.

- Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children, 29-40. Sage Publications.

- Gilkerson, J., Richard, J., Warren, S., Montgomery, J., Greenwood, C., Oller, D., Hansen, J., &

- Paul, T. (2017). Mapping the early language environment using all-day recordings and automated analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26.

- Huey, E. (1908). The psychology and pedagogy of reading. First edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Isaacs, J.B. (2012). Starting school at a disadvantage: the school readiness of poor children. Center on Children and Families at Brookings.

- Kirch, I., Jungeblut, A., Jenkins, L. & Kolstad, A. (2002). Adult literacy in America: A first look at the findings of the national adult literacy survey. National Center for Education Statistics and the U.S. Department of Education.

- Fountas, A., & Pinnell, G. (1996). Guided reading: good first teaching for all children. First edition. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- National Institute for Literacy. (2007). Early literacy: leading the way to success. Retrieved from https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/EL_policy09.pdf

- National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2017). NAEP reading report card: state achievement-level results. Retrieved from: https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/ reading_2017

- Payne, R. (2010). Research-based strategies: narrowing the achievement gap for under-resourced students. Second edition. Highlands, TX :aha! Process, Inc.

- Rasinski, T. (2003). Parental involvement: key to leaving no child behind in reading. The NERA Journal 39 (3), 1-5.

- Whitmore, J. (2002). Coaching for performance: GROWing people, performance and purpose (3rd ed.). London ; Naperville, USA: Nicholas Brealey.